How quickly we use energy is one of our biggest net positive or negative impacts on our world. The slower we consume energy, the better. Measuring our energy parsimony—how slowly and wisely we use energy—helps us make progress on the pathway to sustainable energy. But even before we know exactly how fast we’re consuming energy, we can be sure that taking practical steps to slow down our energy use is a good way to begin our journey on this pathway.

Solar, wind, and water power provide endless energy without pollution. These clean renewable resources are our sustainable energy future. We’ll reach our destination much sooner if we start with practical steps for energy conservation and energy efficiency to increase our energy parsimony, and then electrify everything. The good news is that harnessing clean energy is inherently efficient—unlike burning fossil fuel, which is inherently wasteful.

How quickly do we really need to use energy to live well? Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory estimated that in 2021 the United States used three times as much energy as we actually needed, mostly because burning fossil fuel is so inefficient. Our transition to renewable power can be affordable and fun if we take practical steps to become more energy parsimonious (i.e. slow down our use of energy):

We can conserve energy by making choices that use less energy but require some sacrifices, such as riding a bicycle instead of driving a car.

We can be more energy efficient by making investments that allow us to use less energy without sacrificing comfort, care, or convenience, such as by driving an electric car instead of an internal combustion engine car.

Energy conservation and efficiency give us a huge head start on the pathway to sustainable energy, allowing us to do more with every kilowatt hour of electricity we generate from the sun, wind, and water. In this week’s action guide, we’ll review some facts about energy, power, and parsimony that will enable us make informed decisions, then share specific steps we can take to improve our energy parsimony.

Weekly Poll: How Much Power?

This week’s poll is a hard one—kudos to you if you’re able to figure out how much total power your household demands. It’s actually quite useful to know for both environmental and financial reasons; for instance, your local utility needs to know the answer to ensure their systems remain reliable and their profits remain secure. But you’ll probably need to dig out utility bills and credit card statements to get a full picture, unless you have a sustainability app that helps you track your energy use.

Energy Equivalent of Fuel Economy

Fuel economy is measured in miles per gallon. The higher our fuel economy, the better. Getting 50 miles to the gallon is better than getting 35 miles per gallon. We could flip it around and measure gallons per mile. Then we’d say it’s better to burn 0.020 gallons per mile than 0.029. But it makes sense to express fuel economy so that a bigger number is better, plus it’s handy to know how many miles a gallon of fuel will take us.

Energy parsimony is the same idea: it’s handy to know how long we can operate our household per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity. This will become increasingly useful as we electrify everything and batteries become a bigger part of our lives. We’ll know how many kWh our battery storage system can store, and we’ll want to know how long that amount of energy will last to operate our homes and vehicles.

Power and Parsimony

While most people understand miles per gallon as units to measure how quickly we use liquid fuel (a particular form of stored energy), fewer people understand the units for measuring how quickly we use energy in general. Developing a deeper understanding of energy empowers us to become wiser energy consumers.

Power is energy per time; the standard unit is a watt—one joule per second. Often we’ll want to make apples-to-apples comparisons among different types of energy over different amounts of time. We can use watts to do this:

Burning 500 gallons of heating oil per year is almost 74 billion joules (GJ) of oil energy per 31.5 million seconds, or about 2,333 watts—and that’s about 2.33 kilowatts (kW).

Burning 10.4 gallons of gasoline to drive a car 260 miles per week is about 1.4 GJ of gasoline energy per 604,800 seconds, or approximately 2.25 kW.

Using 16.43 kWh of electricity per day (24 hours) is approximately 0.685 kW.

To compare how quickly we use energy, whether fuel or electricity, we can convert it to kW to have a common reference point. In the example above, we can see that heating oil is having the biggest impact on our total energy use. That knowledge allows us to focus our time on sustainability action that does the most good.

Energy parsimony is the opposite of power: how slowly we use energy rather than how quickly. Technically, energy parsimony is “unit of time per unit of energy,” the inverse of power, which is “unit of energy per unit of time.” Expressing our energy use as parsimony (rather than power) reminds us that making energy last a long time is better than using it up quickly. To make meaningful comparisons about energy parsimony, we can convert all the ways we use energy to a consistent unit.

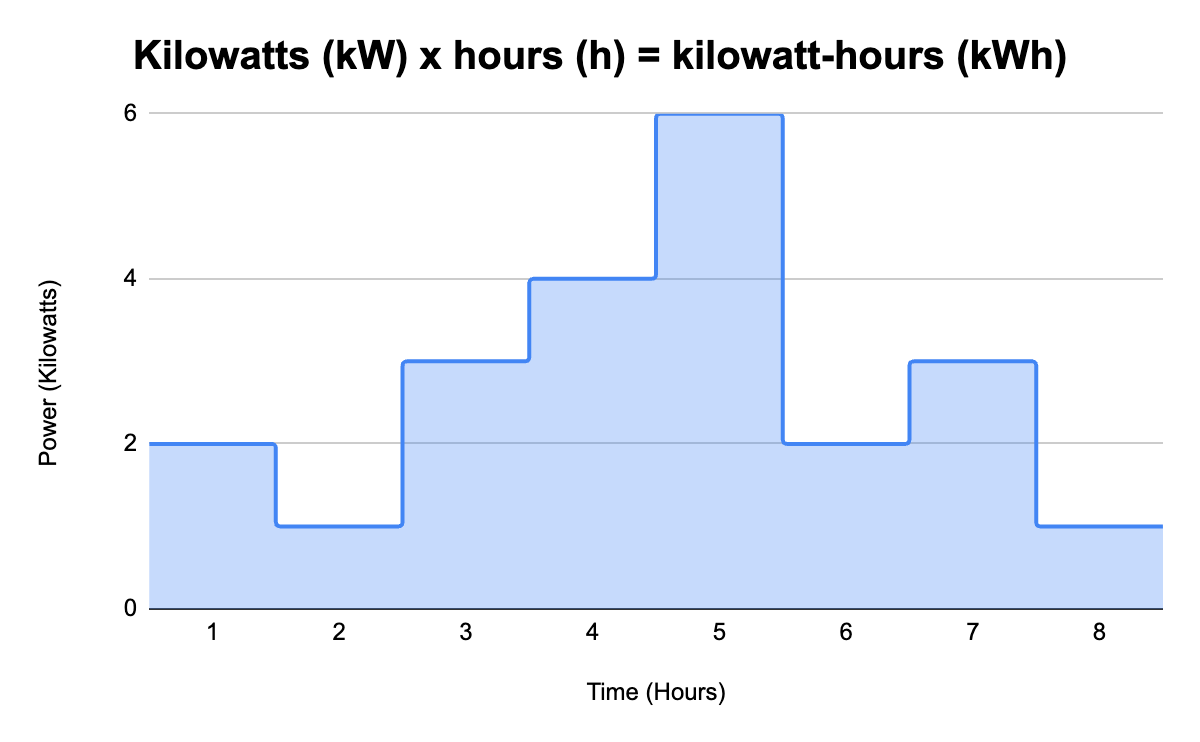

A Kilowatt for an Hour = 1 kWh of Energy

The metric unit of energy is a joule, but since it’s so easy to measure power in kW and time in hours, it’s customary to multiply those together and express energy as kWh. Using a kilowatt of power for an hour of time is a kilowatt-hour (kWh) of energy.

When we calculate our energy parsimony we can use minutes as our standard unit of time, and kWh as our standard unit for energy. For example, if over a year we use 500 gallons of heating oil, we can say our heating oil energy parsimony is a little more than 25 minutes per kWh. To calculate this value we just need to know how many minutes are in a year and how many kWh are in 500 gallons of heating oil. (By the way, the forthcoming sustainability app and handbook from Sustainable Practice will make it easy to do these calculations so we can track our energy parsimony.)

If we increase our heating oil energy parsimony to 30 minutes per kWh we would decrease our heating oil use to 429 gallons per year. Energy parsimony is like fuel economy: if we increase fuel economy from 50 miles per gallon to 55 miles per gallon and drive the same number of miles, we use less fuel.

Looking ahead on the pathway to clean energy, we can anticipate that we’ll replace equipment that burns fossil fuel with equipment that uses electricity from clean renewable sources. Using kWh as our common unit of energy will allow us to make meaningful comparisons and smart decisions when planning upgrades.

Peak Power and Batteries

While, in general, it’s best to focus on increasing our energy parsimony over the long term, occasionally we need to consider how fast we can use energy in an instant. The maximum rate we use energy is called peak power; this rate has different customary units depending on the equipment:

Horsepower is customary for cars; one horsepower is about 745 watts.

British Thermal Units per hour (BTU/hr) is customary for oil boilers; one BTU/hr is about 0.293 watts.

Tons of ice is customary for air conditioners and refrigeration; one ton is about 3,520 watts.

Our buildings also have a peak electrical power load they can handle. The limiting factor is based on volts and amps. If we try to push too many amps through a wire, it could melt. So electrical panels have circuit breakers; if we try to pull too many amps over a wire, the breaker will trip, safely stopping the flow of electricity.

Most homes in the United States have 240 volt single split-phase electrical service, which means the total peak electrical power that a house can use depends on the amps the electrical service can supply:

A 100-amp service panel can supply 240 x 100 = 24,000 watts (24 kW) of power.

A 200-amp service panel can supply 240 x 200 = 48,000 watts (48 kW) of power.

Batteries can help smooth out peak power spikes. If a public power grid supplies our electricity, we could lower our peak power demand on the grid by charging a battery when we have low power demand and discharging the battery (supplying part of our demand) when we have high power demand.

Saving Energy

We can get the best return on investment by focusing on saving energy when we heat and cool buildings and drive our vehicles, typically our largest energy uses.

We can also save some energy by choosing which goods and services we buy. Price is a rough but imperfect guide—in general, more expensive goods and services require more energy than cheap ones. On the other hand, buying lots of disposable products can use more energy than buying durable products. It all depends.

Conserving Energy: Less Fun

One way to make our energy last longer is to use it sparingly, sacrificing comfort or convenience. A famous example is President Jimmy Carter encouraging Americans to put on a sweater and turn down the thermostat. This is energy conservation. It’s easy to conserve energy if we’re willing to accept adversity or deny ourselves pleasure. We can

Turn down our thermostats in the winter—be a little colder but use less energy.

If we have air conditioning, turn up our thermostats all summer—or open a window or use a fan instead of running the AC.

Walk, bicycle, carpool, or take public transit instead of driving our own car.

Combine trips to minimize the distance we drive.

Drive at slower speeds to improve fuel mileage.

Turn down the temperature of our hot water heater so it uses less energy.

Take shorter, colder showers to use less energy for hot water.

Enjoy “staycations” instead of traveling to distant vacation destinations.

Simply by saving money instead of spending it, we indirectly conserve energy. The less stuff we buy, the less energy required to make and ship stuff for us.

Improving Efficiency: More Fun

Another way to save energy is more fun—increase our efficiency. We don’t have to sacrifice comfort or convenience if we use clever techniques or better technology to make our energy last longer. We can

Use a smart thermostat to turn down the heat automatically when we’re not home or at night when we’re tucked under the covers.

Install a more efficient heating and air conditioning system that uses less energy to deliver more heating and cooling.

Insulate our homes so that less energy leaks in and out.

Keep our car tires at the correct pressure.

Upgrade to an electric car that uses less energy per mile than a fuel-burning one.

Upgrade to a heat-pump hot water heater that uses less energy to deliver more gallons of hot water.

Upgrade shower heads and faucets to EPA WaterSense standards to use less hot water.

Install LED lighting with built-in motion sensors.

Upgrade to Energy Star appliances.

With efficiency, we can enjoy a higher quality of life and greater energy parsimony. In some cases, buying higher quality products that last longer indirectly increases energy efficiency by avoiding the need to manufacture and move so much stuff.

What’s Still Ahead on the Pathway…

Earlier this year, we explored the pathway to sustainable movement; now we’re exploring the related pathway to sustainable energy. What are the best ways to save, use, and make energy? Stay with us on the journey to sustainability as we take action to have a positive impact on the world.

References and Further Reading

Update 2022 – A fundamental look at supply side energy reserves for the planet, Marc Perez and Richard Perez in Solar Energy Advances

Electrify Everything, Regeneration

Using Waste Engine Heat in Automobile Engines, The American Society of Mechanical Engineers

Energy Flow Charts, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Fueleconomy.gov, US Department of Energy

Split-phase electric power, Wikipedia

2020 RECS Survey Data, US Energy Information Administration

Jimmy Carter and the “Malaise” Speech, Bill of Rights Institute

WaterSense, US Environmental Protection Agency

ENERGY STAR, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency